Economic model

An OVN implements principles of the p2p economy, also called in the literature the collaborative economy or the participatory economy. Thus, this new economic model embodies new processes for sourcing, innovation (creative work), production, dissemination (or distribution) and capturing of benefits, as performed by open networks, i.e. by free agents who voluntary participate in permissionless processes.

Its mode of production is commons-based peer production or peer production (when the infrastructure used is under the [[nondominium] property regime).

Main theoretical tenants

First, please consider the notion of value, then come back to read further.

The possibility of stable, sustainable open networks at global-scale is no more questionable, they exist in almost all spheres of human activity. The poster child of this movement is the Bitcoin network. There are reasons to criticize some of its features and even its path of development since its launch in 2008, but there is an architectural pattern of this network-type organization and of its economic model that is prefigurative of the p2p economy:

- Property - The network's property regime is neither private nor public, but nondominium, i.e. it belongs to no one, but anyone has permissionless access, under a given set of rules that are immutable (baked into the protocol).

- Transparency - Everything about the network (software, processes, development activities, etc.) are accessible to anyone.

- Openness - Anyone can join the network as a minor (contribute to the physical infrastructure), developer (contribute to the software on which it runs), user (create a wallet and transact), secondary service provider (offer other services on top of the network).

- Meritocratic Governance - Those who contribute to sustain the physical infrastructure of the network, the minors, have the ultimate say on decisions pertaining to the evolution of the network.

- Genesis - The network has been bootstrapped without traditional mechanisms like venture capital or public funding, and the market has not been a necessary tool for its growth, although crypto markets that have been created after have been instrumental in accelerating the growth.

- Transnational - Escapes traditional regulatory frameworks put in place by Governments or intergovernmental/international treatise.

If we listen carefully to Ronald Coase, we can understand why open networks are possible. In essence, the Internet reduces transaction costs among economic agents. We join other individuals into an arrangement, we join organizations, or we centralize to reduce the costs of transactions, so that we have more to gain than if we operated independently. But Coase still talks about firms and markets, not about networks. In some sense, he says that individuals can operate as independent freelancers, transacting on the open market, if the cost of transactions are sufficiently low, so that no extra advantage can be gained by operating within an organization.

Fundamentally speaking, the new potential for new modes of production (new type of organizations, new economic logic) to exist comes from disruptions in three key areas:

- Communication: The Internet makes possible many-to-many communication at global scale, in a p2p way (i.e. non-intermediated).

- Coordination: The Internet makes possible stigmergic coordination, allowing huge numbers of individuals to swarm into action like never before.

- Collaboration: The Internet allows many minds to think together, many arms to swing together. In other words, it gives rise to social intelligence, makes possible massive crowdsourcing and facilitates the deployment of complex activities based on stigmergy.

In his book The Wealth of Networks, Yochai Benkler advances a powerful hypothesis, that lowering the capital requirements of information production (which is the case in the digital era)

- reduces the value of proprietary strategies and makes public, shared information more important,

- encourages a wider range of motivations to produce, thus demoting supply-and-demand from prime motivator to one-of-many, and

- allows large-scale, cooperative information production efforts that were not possible before, from open-source software, to search engines and encyclopedias, to massively multi-player online games.

Felix Stalder explains how Clay Shirky's amends Yochai Benkler's take:

- There are limits to the scale particular forms of organisation can handle efficiently. Ever since the publication of Roland Coase's seminal article ‘The Nature of the Firm’ in 1937, economists and organisational theorists have been analysing the ‘Coasian ceiling’. It indicates the maximum size an organisation can grow to before the costs of managing its internal complexity rise beyond the gains the increased size can offer. At that point, it becomes more efficient to acquire a resource externally (e.g. to buy it) than to produce it internally. If these costs decline in general (e.g. due to new communication technologies and management techniques) two things can take place. On the one hand, the ceiling rises, meaning large firms can grow even larger without becoming inefficient. On the other hand, small firms are becoming more competitive because they can handle the complexities of larger markets. This decline in transaction costs is a key element in the organisational transformations of the last three decades, creating today's environment where very large global players and relatively small companies can compete in global markets. Yet, a moderate decline does not affect the basic structure of production as being organised through firms and markets.

- Shirky develops this idea into a different direction, by introducing the concept of the ‘Coasian floor’. Organised efforts underneath this floor are, as Shirky writes,"valuable to someone but too expensive to be taken on in any institutional way, because the basic and unsheddable costs of being an institution in the first place make those activities not worth pursuing". Until recently, life underneath that floor was necessarily small scale because scaling up required building up an organisation and this was prohibitively expensive. Now, and this is Shirky's central claim, even large group efforts are no longer dependent on the existence of a formal organisation with its overheads. Or, as he memorably puts it, "we are used to a world where little things happen for love, and big things happen for money. ... Now, though, we can do big things for love". (http://www.metamute.org/en/content/analysis_without_analysis)

- Imported from P2P Foundation wiki

Michael Feldstein adds: when costs of participation are low enough, any motivation may be sufficient to lead to a contribution. That this is the key to understanding both Coase and Benkler, both capitalist firms and open source communities.

From Tibi's older writings:

- The type of organizational arrangement depends on the type or the area of activity. Thus we can form private, public, cooperative (co-ops) and non profit organizations. We live in cities, build nation states and form international alliances. Today, we can also organize as global, transnational open networks. There is a blueprint for every type of organization, which prescribes a set of relations or roles, policies, methods and procedures, infrastructure and tools, as well as capturing and redistribution mechanisms for valuables. People decide to restrict their individual autonomy by entering in relation with others according to an organizational blueprint, that is to join an organization, to increase their collective capacity beyond the sum of their individual capacities and, in doing so, to benefit from their collective output. If they don't gain in capacity and benefits, they will likely operate alone until a new form of organization that provides greater advantages emerges, if possible.

Tibi's argument is that one of the drivers for collaboration is not only access to benefits of various kinds, which relates to motivations and incentives, but also the desire to do more, to have a greater impact. This collaboration can happen in various settings, using traditional organizations (where Coases analysis applies) or open networks (where Benkler's analysis applies, with the additions by Shirky). But collaboration must be possible, so Feldstein's maxim stands, the costs of participation are low enough. But people collaborate even if costs are high, in some cases, if the stakes are high, if they are driven by a shared purpose let's say, as long as the shared goals are reachable. Sometimes the organizational form that they chose to adopt can depend on other factors, which are not economic in nature, but relate to other shared values, like privacy or anonymity for example. The benefits that people seek may not be economic in nature, but spiritual for example. In the end, people are seeking to achieve their goals, which may require capacities that surpass the individual, in ways that aligned with their needs and values, and benefit from that, in various ways that every participant perceives. This is what we call, in OVN language, a value experience.

The Internet with the recent p2p technologies (blockchain and others) that the open culture has built on top of it make open networks a new possible arrangement, where the cost / benefit ratios for a new type of global scale collaboration is favourable. Open networks do exist and some of them are highly innovative and very efficient in production and distribution, or dissemination, of their outputs. How can we understand this fact?

- The open source movement has democratized 3D printing and DIY drones and has created blockchain, which are some of the most disruptive technologies in the past two decades. Also, despite the negative press on Bitcoin related to its energy consumption, it only represents a small fraction of the energy consumption of the banking system. It is also the most secure exchange network that humanity has ever produced.

Yochay Benkler identifies two reasons for understanding why open networks can outcompete traditional organizations. The first one is related to what economists call information opportunity cost. In essence, it says that open networks perform better in complex situations where a lot of information needs to be processed in order to seize opportunities and produce good responses to events. The second reason refers to what economists call the resource allocation problem. Open networks do better in matching skills to tasks and allocating resources to the right activity.

Li and Seering (2019) also found that an open community reduces costs and shortens the time to market with five mechanisms:

- OS community members can help decrease the risk of product failure by providing product testing feedback,

- OS community developers can help reduce internal R&D costs,

- the OS community helps to reduce marketing and sales costs by introducing OS products to ideal potential customer pools,

- the OS community represents a talent pool for recruitment, which saves on recruiting costs, and

- the OS community provides resources for product customer channels and partnerships. Reference paper.

All the above justifies why peer production can exist within capitalism or socialism and how it can displace, to a certain extent some firms, through decomodification (offering open source solutions that replace products and services). But this still cannot explain how peer production can reproduce itself outside capitalism or socialism.

In ancient times, the tribe's socioeconomic structure was effective when the in-group was less than ~150 people, and one could remember reputation, debts and favours for each member of the tribe. This is called the Dunbar number. Since then, religions, nation-states, and corporations have all taken our ability to collaborate on shared goals to new levels of achievement. Today, Michel Bauwens speaks about peak hierarchy: horizontality is starting to trump verticality, it is becoming more competitive to be distributed, than to be (de)centralized. If we go back to Ronald Coase, hierarchies have higher costs due to excessive overhead for bureaucracy (an army of paper pushing middle men), a lack of transparency, coherence, speed & efficiency. Open networks seem to be poised for domination.

All these transformations are not just the desire of a group of individuals, they are not driven purely by ideology. They happen because the conditions are right, because a new potential exists and people all over the world respond to it, intuitively understanding the benefits that it offers. But disruptive changes are usually met with resistance. Sooner or later those who benefit from the status quo come to understand the threat that the change poses to their situation and they start to oppose it. A conflict takes shape between them and those who already benefit from the new potential. The church opposed the enlightenment by denigrating the scientific method and by banning the printing press, trying to stop the spread of new ideas. Monarchs opposed the shift to parliamentary democracy and free market economy fuelled by the industrial revolution. Today, states go after cryptocurrency which symbolizes the movement of decentralization. In all these cases, a technology was at the heart of the movement: the printing press for spreading non-dogmatic ideas, the steam engine for spreading new modes of production, the Internet for facilitating new ways of organizing. It is easier to crash a movement that is solely organized based on ideas. History shows that it is almost impossible to stop a diffused transformation based on a new potential.

In sum, we are witnessing the emergence of a peer-to-peer society, which has its own load of good and bad. On the good side of things, it strikes a balance between the individual and communities. It transfers power to the individual, allowing open access to participation in all socioeconomic processes, within the boundaries of community, or network, self-imposed rules.

At the economic level, individuals in a p2p society have the ability to coordinate their efforts, transact among themselves, co-create and distribute their creations, while bypassing hierarchical and closed intermediary institutions, thus escaping the established power structure, which is designed to perpetuate economic dependence. We are witnessing the emergence of a new mode of production, commons-based peer production or peer production (not exact synonyms!), the formation of a p2p economy.

When it comes to material production, digital fabrication allows small groups of people to create local capacity for production at very low cost. Fablabs and makerspaces are local production units that go in that direction. This is coupled to access to global supply markets for key components. These small groups are interconnected via the Internet to coordinate innovation (open source development).

The underlying economic model depends on the type of value network.

Read also Open Value Network: A framework for many-to-many innovation

Sharing, collaborative and participatory economy

Distinctions.

There is a lot of confusion between the sharing, the collaborative and the participatory economy. In fact, you can see it on this Wikipedia page. here we propose some distinctions based on experience within the Sensorica OVN and other peer production systems in operation today.

The semantic separation between the terms sharing economy and the other two seams to be greater than the semantic separation between collaborative economy and participatory economy. In other words, people tend to use the terms collaborative economy and participatory economy interchangeably, but sometimes in opposition to the current use of the term sharing economy. This Harvard review, states that sharing economy is a misnomer, and with their conclusion to replace it with the term access economy. The term micro-service economy is also used in the literature.

When we speak about the sharing economy we put the emphasis on assets (material or immaterial) that are "shared" (redistributed or circulated) among individuals and/or organizations, which in turn share information among themselves about needs and offers, about the location (physical or virtual) of these assets and about rules of engagement or terms of use. The term sharing is used somewhat abusively, not necessarily as a reciprocal relation. In this context, sharing can be a transfer (gift or barter, monetary exchange), or rent (payment for use). The use someone makes of these assets is, for the most part, irrelevant, as long as the integrity of the asset is preserved (when it is rented), and the access respects the basic rules of engagement. The use can be personal or part of a commercial activity and the provider can be an individual or an organization. Some platforms that facilitate access and transactions can be agnostic to that, some of them use strict rules to enforce p2p, b2b or a combination. Critics of the sharing economy propose alternative terms such as access economy, rental economy or micro-service economy. These critics focus on the lack of reciprocity as well as on the lack of social externalities that are normally created through reciprocal sharing.

When we speak about the collaborative economy, the focus is mostly on the allocation of time for a common output. More concretely, we think about people producing something together through a process that minimizes exchanges (often mediated by monetary currencies). In other words, in its purest form, no one is paying anyone else for doing something, and usually no one can monopolize the output. Classical examples are Linux, Wikipedia, open source software and hardware development, etc. There is a lot of cooperation in a traditional company setting, but everyone involved engages in an exchange process, trading skills/time for money. For this reason, this is not a collaborative economy example.

There can be rules about how the output of a collaborative process can be leveraged by others to generate wealth. A good example is RedHat that offers consultancy, installation, and maintenance of IT systems built on Linux. These rules come in the form of licenses, which range from no restrictions at all, to non-commercial usage.

This concept of the collaborative economy can be extended to other forms of contributions, which can range from financial (ex. crowdfunding), to material (ex. sharing a 3D printer with a group to prototype something). In this case, making available these tangible and material assets constitutes a contributions, and their use is directly related to the collaborative activity, i.e. it is project/venture specific, unlike the case of the sharing/access economy where the type of use someone makes of the "shared" asset is most of the time irrelevant (can be personal use). Moreover, these tangible resources used as contributions don’t necessarily exchange hands in the process, there is no transfer of ownership and they are not rented, these resources are shared within the group for common use. There can be rules related to the redistribution of potential benefits based on these tangible and material contributions, which can take the form of public recognition (ex: “a big thank to such and such for having contributed with the physical space and the 3D printer”), or equity - a promise of future benefits, see Benefit redistribution algorithm.

The term participatory economy putts more emphasis on the process through which something is collaboratively created. This process is open, i.e. it has very low or no barriers to entry (ex. the Bitcoin permissionless network) - more on openness. This is proper to the OVN model developed here and implemented within Sensorica for example.

A classical co-op can be the locus of collaborative production, making open source artifacts (material or immaterial), but access to participation in the process can still be invitation-based or conditioned by a strict filter. This is how the Enspiral network and las Indias operate. Co-ops are not open or permissionless networks. The participatory economy is more a set of relations that grant access to collaborative production processes to anyone that can deliver, no other questions asked.

- Attribution: remixed from The sharing, collaborative and participatory economy: what are we talking about? - Sunday, May 29, 2016, Multitude Project Blog

Property

Different forms of property are used within the OVN, see more on the Property page.

Material contributions and private property

Affiliates can contribute to processes, in the context of a venture, using their own their material resources (ex. physical space, equipment, tools, consumable materials, etc.). These assets can be listed as available for use in a pool of shareables, with rules of use. The notion of individual ownership can be preserved and the owners can set their own rules of access/use in order to protect their assets (some conditions related to network-level and venture-level governance may apply). When these resources are used by any affiliate, or consumed, a contribution is recorded for the owner. We call this a material contribution, which is a form of transaction (in NRP terms) but it is not an exchange process, as in renting an asset. Also, there is no debt generated towards the owner, incurred by the venture for using the asset. Some have advocated a hybrid model of exchange + contribution). We can see the pool of shareables as an amalgamation of individually owned material resources to be used by affiliates or consumed in a process. This concept of material contribution can be extended to shared property, in which case the contribution is attributed to all co-owners, and the benefits that may follow from it will be split among all the co-owners, based on a scheme of their choice.

Individually owned or co-owned assets can also be transferred to a Custodian, usually a non-profit organization, a trust. In this case, the Custodian becomes the legal owner of these assets and protects them from capture (being seized by other private interests), while making them available to all affiliates, based on a set of rules. This is the nondominium form of property, which is also extended to immaterial assets, like brands for example. Formally speaking, the Custodian signs a Custodian Agreement by which it obliges itself to manage these assets in the interest of all OVN affiliates, and promises to transfer all the assets it holds for the OVN to another entity, if affiliates aren't satisfied with its services, under the same nondominium regime.

Digital assets (ex. documents, presentations, design files, software, pictures, videos, etc.) produced by the OVN are shared under some type of open/free or Creative Commons license, and become part of the OVN's commons. Commons in digital form have low maintenance and stewardship costs. Moreover, their distribution or dissemination cost is nearly zero. Thus, these are shares assets that don't require much governance to process.

See [CAKE], the Custodian of Sensorica.

About resources

See also Resource types in the context of the contribution accounting system

In terms of available resources, OVNs are very elastic, as in pure p2p mode everything is crowdsourced.

OVNs are unbounded organizations, which comes from their openness (in terms of permissionless access to participation). Their transparency (in terms of access to information) allows needs to propagate through the ecosystem, which can attract new participants (agents or affiliates) to make different types of contributions, because they can, since the network is open. In that sense, the network is not bounded by a limited pool of resources (ex. budget, physical space, equipment capacity, number of employees, etc.) like traditional organizations. Its resources can expand very dynamically based on needs and depending on the incentives that are provided.

Human resources

OVNs are open (in terms of access to participation) and transparent (in terms of access to information), and run on an Internet-based platform. OVNs that focus on high tech development (material of software) can operate in the long tail] mode of production, meaning that they can integrate a large number of agents distributed across the planet. In other words, their pool of participants is practically the world's population.

See also the Role system, Reputation system - [NOTE to participants: expand on this...] discussion for this page

Knowledge commons

See Commons.

Resource allocation

See Yochay Benkler's second advantage of open networks: resource allocation.

An OVN is decentralized in terms of allocation of resources. In other words, most of the resources used in its processes are under the private property regime and are provided by affiliates (as original owners of these resources), in the form of contributions. Some of these private assets are lumped as pool of shareables, another property regime, in order to harmonize their access and rules of use by any affiliate contributing to a venture within the OVN. Like in traditional open source projects, every affiliate decides where to allocate resources for reasons that are purely individual and/or collectively agreed upon. Yet other resources come as commons or nondominium.

In the pure p2p form there is no budget for a venture. If cash is needed for something (pay for a service or for a piece of equipment, if it can't be sourced within the network as a contribution) a crowdfunding process is used, and those who participate can decide to turn that into a financial contribution. See also discussion on empathic access.

In practice, Sensorica has used grants, in fiat currency, which have gone into a shared funding pool, a budget, administered by a Custodian, with input from affiliates. Thus the Custodian offers financial services to ventures within the OVN, holds funds in its bank account and administers them according to the collective will of venture affiliates, based on priorities and/or planning, which must be public. Distribution of funds from a shared budget associated with a venture is also contingent on emergent priorities and / or planning. Crowdfunding a venture also produce a shared pool of monetary assets that needs to be managed by the venture's affiliates.

DAOs use web3 financial primitives in conjunction with on-chain voting mechanisms for funds allocation. Often, a proposal process is used, where agents present an action plan with a budget and other agents affiliated with the DAO vote to accept or reject the proposal. In this case, the fine administration of the budget is left to those who execute the action. Some oversight or quality check or auditing can be applied.

When it comes to holding shared material assets (physical spaces, equipment and consumables) for peer production, Sensorica implements the nondominium form of property. These shared material assets legally belong to the Custodian, which acts as a trust, guaranteeing access to affiliates and preventing capture. The rules that govern the access (to use) are decided by affiliates through some governance process. The network also decides to allocate funds for maintenance, replenishment, and new acquisitions of shared material assets. These activities are, in general, performed by network affiliates. Sensorica offers paid use to some of these production assets (equipment) and percentage of the revenue generated by this commercial activity is extracted and kept for maintenance (materials and work). The Custodian is not allowed to exploit these shared resources for its own benefits, and this is enshrined by the Custodian Agreement.

Currency

See also current-see in this context. More on the Currency page.

The OVN implements peer production, relying on contributions, risk-sharing and expecting benefits in proportion to one's contributions. A contribution accounting system is used to keep track of contributions, and describes how they amalgamate into a deliverable (can be a product). There are no exchanges in a process of co-creation, therefore there is no need of a currency for internal processes, in a pure peer production system. But hybrid models have already been advocated by others.

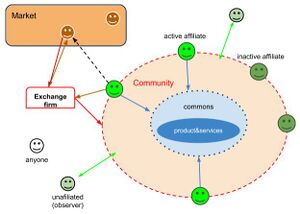

If the OVNs deliverable is a product (an artifact destined to be distributed on a market through monetary exchanges), it will be distributed by an Exchange firm. Other exchange mechanisms can be used: barter, donations, etc.. Tangible rewards that flow back into the OVN is called revenue. All revenue is redistributed to affiliates based on their past contributions or fluid equity, using the contribution accounting system. A portion of that goes to maintain the infrastructure (perhaps transferred to the Custodian). Affiliates can use a portion of their revenue to invest back into ventures, as a financial contribution.

Motivation and Incentive system

OVNs embody a motivation and incentive system that sends specific signals to participants. In terms of incentives, the system couples contributions and responsibility (see Roles) to benefits of different types, including fluid equity, through the benefits distribution algorithm. Central to designing such games is the notion of fairness. Agents engage in games that they consider fair, that treat every player according to them same standards. This is a clear departure from traditional labor theory of value and the utility theory of value, which represents a departure from capitalism and communism/socialism. Affiliates within the Sensorica OVN have responded to extrinsic incentives. One example is the revenue generated by affiliates that engage in commercial activities. A second example is the access to a variety of assets, to materials, tools and equipment, as well as to a pool of talent. A third example is the access to a context for technical and scientific research, allow agents to apply their knowledge, prototype their ideas, create new ventures and accelerate the development process of new solutions, some of which can be distributed as products and services. Sensoricans have also responded to intrinsic incentives. Some affiliates are driven by the interest or enjoyment in the tasks they take, without being subject to any external pressure. Others appreciate the learning opportunities while contributing to ventures. Some affiliates seek recognition from their peers, which comes in the form of formal reputation within OVNs, and is publicly exposed from profiles. OVNs are highly collaborative environment, where individuals share and help each others, which can provide great satisfaction. OVNs also cultivate a high sense of individual autonomy. Since OVNs are transparent (in terms of access to information) they are biased towards ethical behaviour, which provides a good alignment with some individual values. The openness (in terms of participation) of OVNs makes them grow around widely accepted values. For this reason, ventures are often attached to solving important social problems. The mobility within the OVN, and the unrestricted exposure to all the activities give affiliates the possibility to grow their skills and experience.

In all, the system is designed to maintain awareness about the purpose, meaning, and importance of each affiliate’s actions. It is designed to make affiliates conscious about why they are doing what they are doing and to link that to benefits.

NOTE: The above text was adapted from the IGC-HEC case. It was produced by Mai Thai (prof at HEC) in collaboration with Sensorica affiliates.

About the production process

OVNs implement commons-based peer production, or peer production in their most extreme forms, a new, potentially self-sustaining and regenerative system of production.

Resources are used by agents in peer production. Peer production is a process of co-creation or co-production. Unlike in traditional settings, in which process of production rely on exchanges (labour against tangible benefits, money for example), leading to the enclosure of the output by the entity that assumes the risk (the investors in the company for example), co-creation processes rely on contributions, shared risk, as well as shared output. Thus, assets can avoid commidification because they are not exchanged during the co-creation process. Labour is also not commodified in peer production. No one is working for anyone else.

Peer production relies on stigmergy, which leads to self-organizing (emerging role structures) of agents. In such networks, the actions of agents (or affiliates) is coordinated towards a shared outcome, while facilitating access to the resources required in the process. It describes a new model of socioeconomic production in which the labour of agents is coordinated (usually with the aid of the Internet) outside of traditional institutional frameworks. Wikipedia

Peer production alludes to new regimes of property and resource access rules. To accelerate innovation and make production efficient, the flow of resources must be unhindered within the network and channelled towards hubs of production. Thus, there is a tendency to move resources from a private property regime to alternative forms of property such as commons, shared resources and even nondominium. Some call these new properties regimes plural property (of shared goods).

We also need to note that commons-based peer production contains two terms that are associated with two very different political economy movements. The commons side is closer to the traditional left, to communitarism, and puts the emphasis on sharing. The peer side is closer to the traditional right, to libertaniarism, and puts the emphasis on individual freedom / autonomy and private property. Hence commons-based peer production announces a synthesis of these two tendencies, increasing individual freedom and autonomy by putting in place new property regimes, new rules for access and use of resources. See more on balance between the individual and communities.

Some use commons-based peer production interchangeably with the term social production. Wikipedia

See peer production on P2P Foundation.

About marketing

In OVN language we use outreach.

OSH Start-ups’ Business Development Challenges: The Case of Sensorica from a Total Integrated Marketing Perspective, by Normand Turgeon, Mai Thi Thanh Thai, Gheorghe Epuran (temporary restricted to Sensorica members).

From a service perspective

.

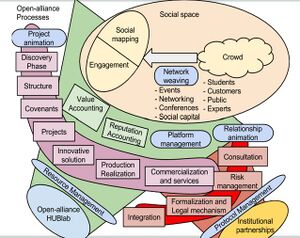

OVN ecosystem mapping

.

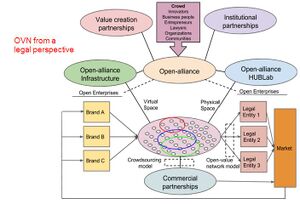

Legal perspective

.

Interfaces

.

About entrepreneurship

See collaborative entrepreneurship.

Economic models and sources of livelihood

See more on Business models.

- Offer DIY kits (can be transactional kit sales) that provide required vitamins (non-digitally manufactured components) to build a particular tool (Zimmermann, 2014; Gibney, 2016).

- Offer specialty parts / components, hard-to-find, custom (ex. BackYard Brains or OpenQCM both sell the most specialized and hardest to source components for their respective open hardware tools).

- Help with calibrating and validating (scientific) hardware (can be transactional service) to provide security to prosumers who build their own tools. This provides prosumers with the confidence that their measurements or functionality are acceptably reproducible, accurate and precise.

- Education / Training (ex. Open Source Ecology), include support. This can also follow the consulting business model (Fjelsted et al., 2012).

- Ecosystem services: provide trust, validation, discoverability, help, a place to discuss and collaborate, etc.

See also open business models patterns.

Products

We normally speak of outputs of OVNs and open ventures in terms of deliverables. In some cases, these deliverables can come as goods and services (products), to be distributed through a market.

OVNs are transparent in terms of access to information about everything, including internal processes and its deliverables, or products for instance. This transparency erases the informational asymmetry often seen between corporations and their market. This informational asymmetry often gives raise to abuse, higher prices and unethical practices. Among other things, this makes possible programmed obsolescence and deliberate environmental negligence (externalities). On the other side, transparency incites for better practices and increases accountability. In the current economy, OVNs can capitalize their higher ethical standards, which are a corollary of their openness and transparency, and can charge a premium on their products, to recover a portion of the loss due to the informational symmetry (which reduces the bargaining power).

Because of transparency, the product design philosophy fits better the widely accepted norms. Openness, which allows a larger participation to the design process, can result in more valuable products (higher quality, user friendly, environmentally friendly, interoperable, etc.).

See Sensorica's product design philosophy document.

See How to play the open game in the present and future economy

Clients

The distinction between producer and consumer or clients becomes fuzzy in the p2p economy. Concepts like prosumers are used to address the bidirectional flow of agents in these two roles. In other words, people can be seen as users for an open source project, even pay for some services related to the delliverable (good or service), and at the same time provide feedback and contributing with ideas for improvement, even get involved in development, since the project is open. This situation is transported in the context of open ventures and OVNs.

If the OVN's deliverable comes in the form of a product (to be distributed through a market - transactions), transparency and openness of the OVN makes possible contributions from clients, same way people can interact with open source projects. In fact, clients are also invited to become contributors to the venture, to convert into an affiliate. Unlike traditional companies, OVNs reward feedback as contributions through the contribution accounting system.

Strategy

See more on Strategy.

Organizational design

The OVN is a network of agents that collaborate on shared goals (for example to design some hardware and disseminate under a Creative Commons license). The knowledge that goes into a deliverable (can be a product) is publicly shared (transparency). Anyone can join to contribute (openness).

Although the OVN’s deliverables are created by individual affiliates, when it comes to products the exchange on the market must be performed in the name of a formal organization, in the current state of our economy. This organization is most often a limited liability corporation, that shields the members of the organization from lawsuits related to production and commercial activities, as well as with the use of the product. This liability issue has been solved in the OVN model by the creation of an Exchange firm. This solution helps alleviate two additional problems. First, affiliates might be tempted to cheat for large commercial deals, not disclosing the real profit. A formal organization built to serve the community can be more reliable, since it is subject to stricter rules, under the justice system, and run by professionals (may be a weak argument...). Second, some affiliates may try to monopolize the interface with the market (access to the market), and therefore gain disproportionate influence within the network. The Exchange firm plays the role of interface with the market and ensures that affiliates have equal chance to access the market.

Affiliates are not paid a salary but they share the benefits from the venture, which can even be monetary compensations if the deliverable is a successfully commercialized product. Affiliates can conduct their own business outside the OVN. A benefit redistribution algorithm is used to distribute benefits to contributors or affiliates. Anyone can become an affiliate by contributing to the venture - openness. Not all forms of participation are contributions. Tangible benefits (ex. monetary compensations) are not guaranteed within an open venture, within an OVN, even when contributions are made. For instance, affiliates are not automatically rewarded for ideas or non-used products/processes. The contributor may benefit in various other ways (learning, gaining reputation, gaining access to governance, etc.). Tangible benefits can come if the venture is funded in some ways (crowdfunding, donations, institutional grants, etc.), or if the venture produces a product that is exchanged on the market. In the later case, revenue is distributed to affiliates when the product is sold. Product and "business" development are the responsibility of active affiliates. Any affiliate can take the lead at his/her own initiative at any stage, from product development to distribution. Active affiliates must assume the task of persuading other affiliates to engage in their venture and/or use the results of their work in the next activities in the development process. At any stage of the value chain, active affiliates can decide whether to source/develop upon an existing product/process from within the OVN or from the market. On the same token, they can decide to sell their work at any stage or get their work used in the next stage. It should be noted that only work whose results get used is compensated when revenue flows back to the value chain. OVN affiliates understand that failure is a part of R&D processes and thus failures for good causes are rewarded by in the form of reputation building. Furthermore, activities with high risks of failure are given higher weight in the benefit redistribution algorithm. Redistribution of revenues from each product is calculated by the OVN’s benefit redistribution algorithm – a part of the OVN’s infrastructure entirely under the control of OVN’s active affiliates - see governance. The contribution accounting system is made of the value, reputation and role systems that interact with each other.

The NRP-CAS captures each affiliate's contribution types (role system); quantity (value system). The role of affiliates within the OVN is emergent (it is not assigned). As a result, the role system incites voluntary subordination and is important for self-organizing. The reputation of each affiliate is the result of peer-evaluation, by all other affiliates, taking into consideration the role played. The evaluation focuses on performance, behavior, drive, etc. The reputation is connected to the value system and affects the ability of an affiliate to extract benefits from the network. The reputation system incentivizes good behavior within the network and helps to focus attention. Therefore, the reputation system plays an important role in the creation and the flow of valuables within the network by filtering participants for adequate tasks. Sensorica’s experience with this contribution accounting system has been positive.

NOTE: The above text was remixed from the IGC-HEC case. It was produced by Mai Thai (prof at HEC) in collaboration with Sensorica affiliates.

Infrastructure

See the Infrastructure page

Growth model

Network level

An OVN grows by affiliation. It's size is only limited by coordination.

In terms of infrastructure, for every venture that creates exchange value a contribution accounting system is used to describe how valuables amalgamates into a deliverables. Deliverables of some ventures can represent inputs for other ventures, in which another contribution accounting system is used.

Network of networks level

The infrastructure of OVNs is designed to be applied to fractal structures, or Network of Networks. An OVN can be considered as an individual contributor in a venture in another OVN . Some have used the term super-value network. In theory, the OVN concept can be applied to the entire global economy.

We are thinking about contribution accounting at the venture level, which is federated at the network level and use a protocol for inter-network exchanges and co-creation.

We observed around Sensorica 2 growth modes for Network of Networks.

- by affiliation - independent networks that already exist affiliate with other networks. See work on the Open Alliance.

- by incubation and spin off - individuals with project ideas join a network, grow their venture, which become sub-networks, use local resources to develop and are spun off once they reach critical mass. This is the case with Drone and 3D Printing projects in Sensorica.

We are now thinking about giving OVNs the internal mechanisms to nest and incubate embryo networks to be spun off later.

See Networks of networks - Tuesday, March 1, 2022, Multitude Project blog

External resources

IGC-HEC case on Sensorica

See event summary Open database of studies and papers

Papers on Sensorica

- OSH Start-ups’ Business Development Challenges: The Case of Sensorica from a Total Integrated Marketing Perspective, by Normand Turgeon, Mai Thi Thanh Thai, Gheorghe Epuran (temporary restricted to Sensorica members).